Wished Meself was Dead

Hunter Longe

20/06 – 3/08/2024

Wished meself was dead

Or better far instead [1]

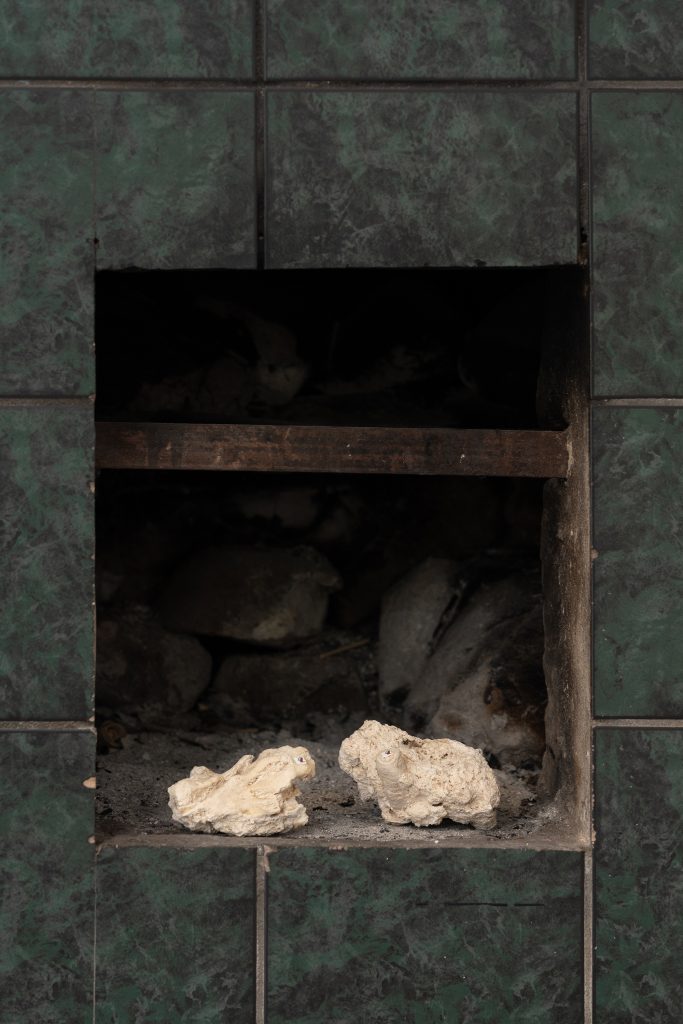

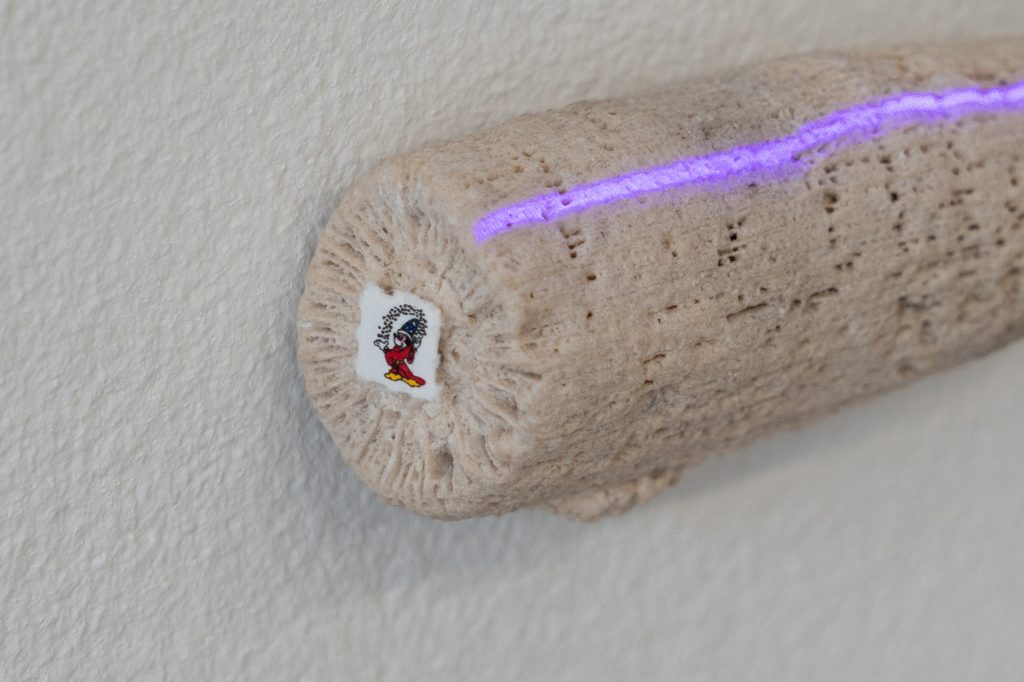

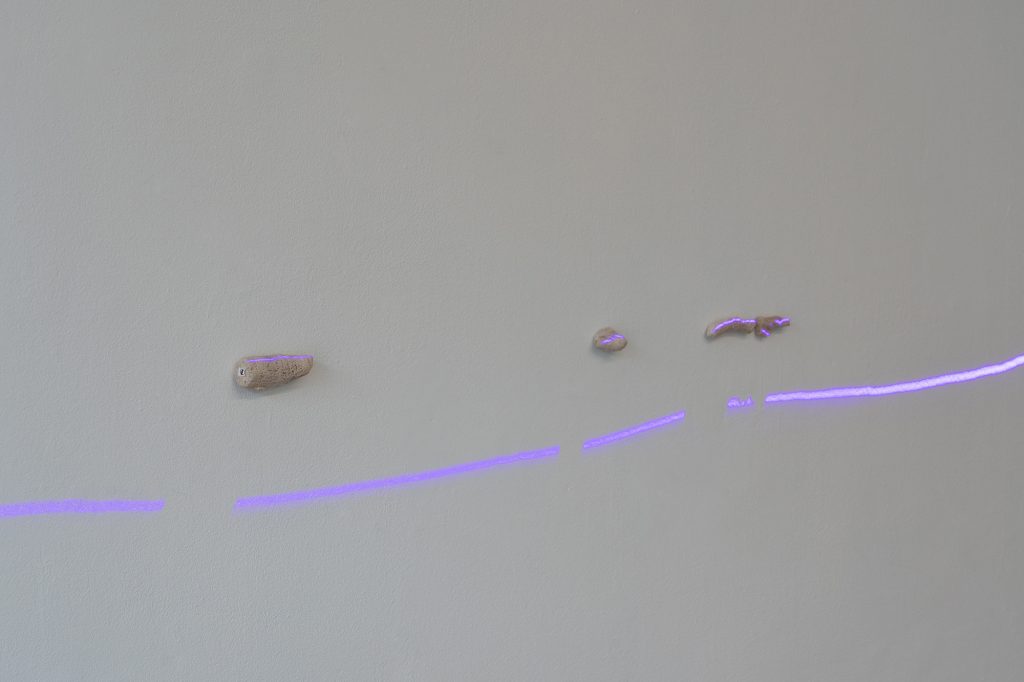

A piece of fossil coral

A 21-million-year-old spine

The past inserts a finger into a slit on the skin of the present, and pulls. [2]

My dad died one year and eleven days ago. He had cancer and in the end, when he was really suffering, he decided to do an “assisted death.” Which essentially means he took his own life by consuming a mix of substances that put him to sleep and stopped his heart. He had two sets of twin boys, I have an identical twin and my older half-brothers are identical twins as well. The four of us and our uncle, my dad’s brother, were in the room with him, singing and holding his hands as he died. It was the most transcendental experience I’ve ever had. Time slipped. Either it actually slowed down or my perception of it was totally altered. Thirteen minutes seemed like two hours.

About six months later, one of my brothers attempted suicide. His survival was a miracle and I am monumentally grateful he is alive and well and back in good health. I felt profound empathy, for I too at times, in the depths of anguish, have wished myself were dead. Needless to say, these trying experiences have greatly impacted me. Thoughts of my brother and father have been conflated with my artistic preoccupations. These days, I wonder how heavy emotions resonate on a universal level, beyond human and into the depths of geologic time. I am curious as to how the occasional yet grave desire to be dead might resonate in the fossil record, and how grief might be petrified.

Sea foam mixed with grief becomes solid [3]

My dad liked the Dubliners, who did a great rendition of the D. K. Gavan song, “Rocky Road to Dublin,” a line of which I have borrowed for the title of the exhibition. When I was a kid I didn’t care much for the song, now it hits hard. I have begun to let my emotions, along with my twin and my father become active in guiding my artistic practice. And I am making an effort to be more perceptive to the ways in which the dead influence the present and even care for the living. I want to honor them and remember them. To do so, I am “resisting the discipline of mourning and rationality.” [4] I try to recognize rationality as a myth and open myself to signs: when I cut an ammonite in half, I see a zygote splitting; the doubling of all the elements in the show are like twins; finding fossils of ancient sea creatures in the regions around Geneva makes me think of my father who would often say, “the ocean is my church.”

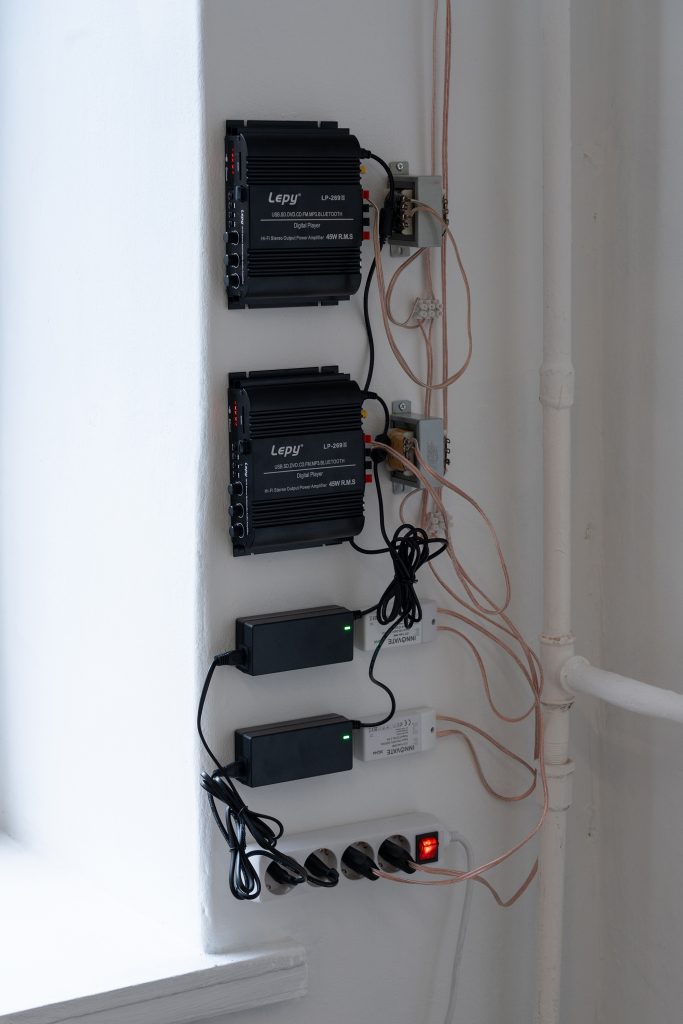

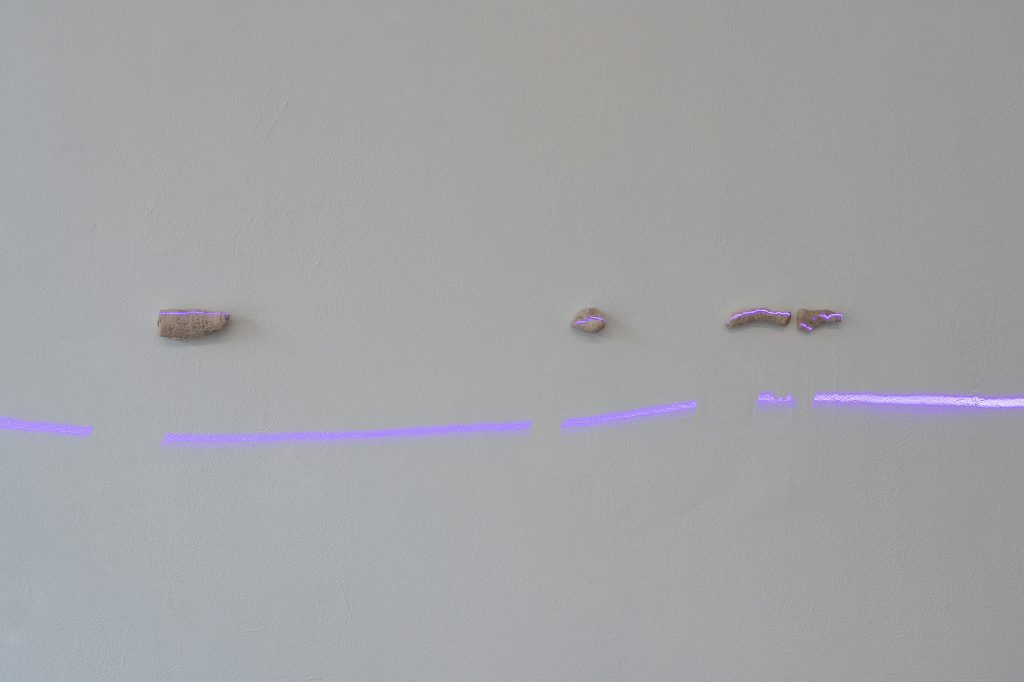

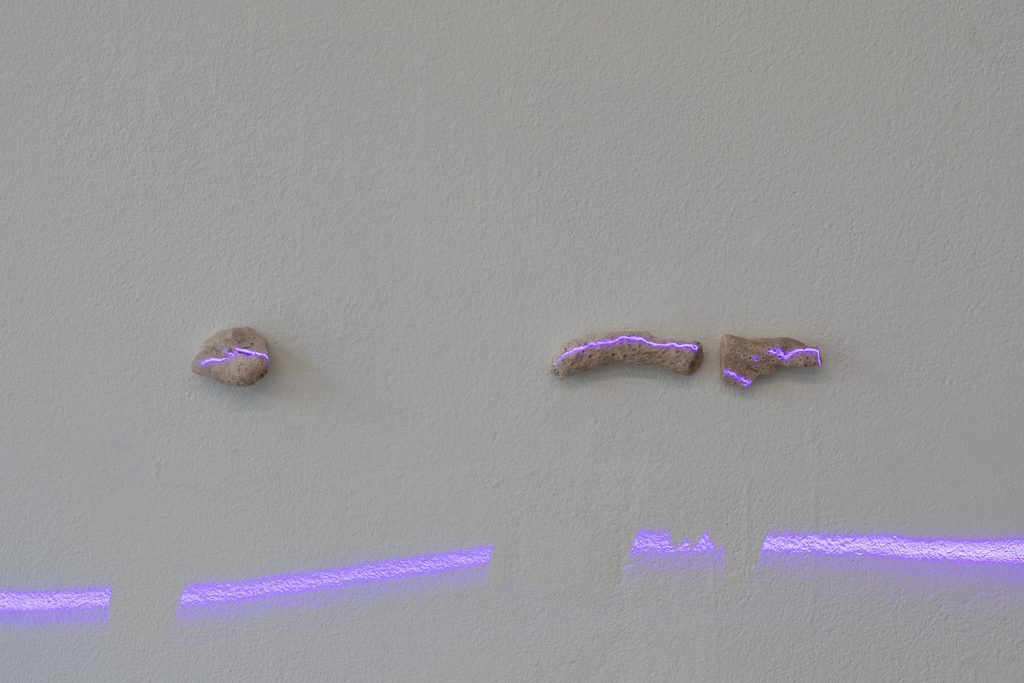

The work, Wave Offering, consists of an audio recording of waves made at the coast near Kalngale, which is being sent through LED lights making them flicker with the frequency of the sound. Two small solar panels placed into this light are plugged into portable speakers, converting the scintillating light back into sound. Light and sound are mediums—in the sense of an artistic medium, but also in the sense of a person or thing between two worlds, through whom the spirits of the dead are alleged to be able to contact the living. Since the advent of electricity, people have perceived messages through it from spirits or ghosts. It seems vulnerable to paranormal activity, a medium through which a less visible world beyond might occasionally make itself known. When talking about mediums in her book Our Grateful Dead, Vinciane Despret says, “they perform presentification, both in the sense of moving the past into the present and of making a presence.” [5] For me, fossils do this work too, while flickering lights bring about the feeling of a “presence,” or at least the potential presence of a presence. I’m using this synesthetic audio-visual medium to offer the sound of waves on a calm baltic sea back to my father, and back to the ancient marine life whose remains inhabit the exhibition.

Incredibly long distances of time fascinate me, probably because they are so hard to fathom. I am talking about spans of hundreds of millions of years. On the surface of the Earth, much rests from distant bygone eras which give hints to the elapse of eons, yet in order to grasp them we must rely on our imagination. It seems that time, existence and reality are matters of the imagination. Imagining the geologic and paleontologic past has forced me to question what we often refer to as “the arrow of time,” the sense that time moves unidirectionally. My questioning comes from a recognition of how the past is ever present, how entities and beings of the past still affect the present. In this way, certain objects and things seem to transcend time, existing both in the past, present and future. My work basically tries to embody this collapsed sense of time, perhaps even suggesting that our human perception of the past is somehow an alteration of it, to a degree which we might say we affect the past.

In her book Our Grateful Dead, Vinciane Despret cites Souriau on the notion of “instauration,” which is somehow to create but also to renew, to create from what already exists. “The artist, he [Souriau] says, is never the sole creator; he is ‘the instaurator of a work that comes to him but that, without him, would never proceed toward existence.'” She explains: “The work seeking existence calls on the painter, poet, or sculptor, and these have to devote themselves to bringing the work to its full completion, so it can be accomplished as a work.” [6] This feeling that the artwork has some agency of its own, that it comes from outside the artist, really resonates with my practice. For Despret, instauration also illustrates a methodology by which the dead play an active role in the lives of the living. Writer and filmmaker JF Martel notes a quite literal example: “our very language, the words we use to communicate with one another, are the relics of the dead.” [7] Consider that the petroleum remains of algae and plankton become packaging, clothes, and fuel; the calcium carbonate marine fossils of shells, bones and coral are the key ingredients of concrete; they are ancient yet integral to modernity.

For me, fossils are like gifts from the past. They inspire me. I “instaurate” with them. Once I hold them in my hands and look at them, they begin to give me ideas about how they might be incorporated into a work or installation. They are active in my practice and in becoming an artwork. Only once encountering two 21-million-year-old fossil whale vertebrae, could I have an idea of what to do with them. In the show, they are like twins in time and eyes of the past slipping into now.

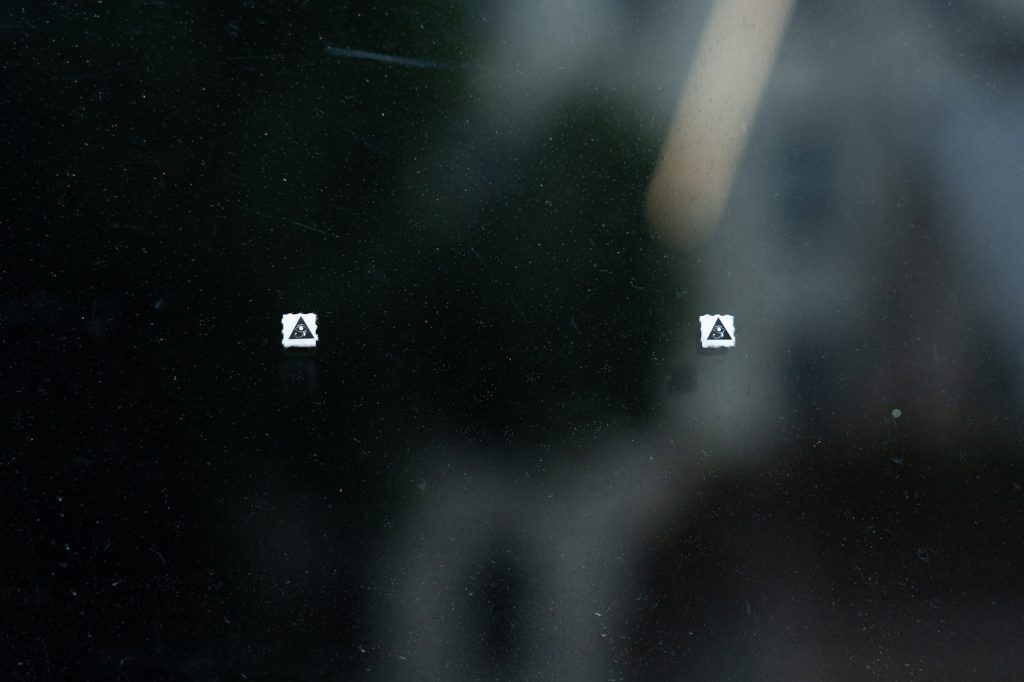

I am interested in facilitating spaces or experiences in which the perception of time might be slightly altered. This effect is achieved through unusual combinations of materials and technologies—things both extremely old and rather new. One morning a few months ago, I woke up thinking of LSD, I must have dreamt of it. It occurred to me that this would be an unexpected material to combine with fossils. But I was unsure. Then a few days later, I came across an audio recording of my father describing his purchase of Owsley Stanley acid on blotter paper in 1969 and the epic trip that ensued. I took this as a sign, which led me to investigate the classic art that adorned LSD blotter paper, a “medium” of another dimension.[8]

On the work Afterlife Navigator (for Brian), the blotter tabs are adorned with the eye of Horace. I probably wouldn’t have included this iconography had I not looked up its history. In Egyptian mythology, Horace lost his eye in a battle with Set, which he then managed to get back and then give to his deceased father, Osiris, to help sustain him in the afterlife. These LSD blotter tabs are affixed directly to some of the fossils. Like this, the counterculture from which I am a descendent is put directly in relation with ancient remains, thus constituting an actual temporal slip.

I am interested in facilitating spaces or experiences in which the perception of time might be slightly altered—offering refuge from the clock-face world of capitalist modernity and segmented time. Exiting rationality a bit, sensing a time slip, the past is more likely to move into the present. Despret says: “modifications of consciousness open consciousness to another level of reality.” For me, this seems to link back to the necessity of imagination in understanding deep time and in opening up to signs and messages from the past and from the dead.

The other day in the cemetery near my studio looking intently at the paths left by some critter on a gravestone underneath a yew tree, I thought, “we are the dead.” Yet, despite my confronting death, it remains the ultimate radical mystery wavering out in the void.

References

[1] Lines borrowed from the 19th-century song “Rocky Road to Dublin” by the poet D. K. Gavan.

[2] Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, 1974

[3] Lisa Robertson, Magenta Soul Whip, 2005

[4] Vinciane Despret, Our Grateful Dead, 2021, pg.70

[5] Ibid. pg.107

[6] Ibid. pg.8

[7] Weird Studies podcast, Jan 18, 2023, episode #138, at 1:05 min.

[8] Erik Davis, Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium, 2024

[9] Vinciane Despret, Our Grateful Dead, 2021, pg.62

Hunter Longe is originally from California (b. 1985) and currently lives and works in Geneva, Switzerland. He has a Bachelor of Fine Arts from California College of the Arts, San Francisco, and a Master of Fine Arts from Piet Zwart Institute Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Recent group and solo exhibitions have been at Centre d’art de Neuchâtel (2024); Soft Opening, London (2024); Kunsthaus Langenthal (2023), Last Tango, Zurich (2023); Sonnenstube, Lugano (2023); Espace 3353, Geneva (2023); Istituto Svizzero, Rome (2022); Krone Couronne, Biel/Bienne (2022); Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève (2021); Musée Cantonal de Géologie, Lausanne (2019); NoMoon, New York (2019); Et al. Gallery, San Francisco (2018); LambdaLambdaLambda, Pristina (2017); Hordaland Kunstsenter, Bergen, Norway (2017). In 2021, a book of his writing and drawings entitled DreamOre was published by Coda Press and he was a winner of the Swiss Art Awards.

Support: VKKF (State Culture Capital Foundation), Riga City Council, the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia

Photos: Līga Spunde