a

drop

in

the

universe

has

universes

of

its

own

Carlos Noronha Feio

9/10 – 8/11/2018

Drop a drop in the universe. Given the cosmic proportions of the subject, the repercussions might well be a set of infinitesimal, albeit infinite, reverberations. A cosmological mise-en-abîme. Portals that open up momentary gateways into parallel universes. Or one of those mirror-encrusted “infinity” rooms where reflections go on and on and on until they’re reduced to the size of a pin prick, and yet they go on.

Lisbon-based Carlos Noronha Feio might not dabble in planetary and star alignments, but the cosmological principles still hold true for the links he untethers when it comes to relationships between cultural insignia, objects, borders and histories across space and time. What, at first, sounds like a series of near unbearable high-pitched electronic trilling – a message from one of those liminal universes – turns out to be a sequential performance of national anthems representing countries whose existence is no longer beholden to a unanimous accordance of geopolitical status, but simply to at least one other state’s recognition. Abkhazia, Kosovo, South Ossetia, Transnistria.

The list – all six hours of it – goes on, compressed into a 20-minute long gallop, the maximal recordable time on one side of a vinyl dubplate. Words, melodies, rhythms – all are garbled into an indistinct, veering on indecipherable, conglomeration of noise. The tragicomedy of it lies in the cartoon-like warble of sped-up voices that soon enough makes way for the realisation that, stripped of any singularity, they become a drop in the ocean (or universe, to keep the image afloat) of time. Which isn’t to say that they’re reduced to a nothing. Quite the opposite. If anything, they speak of the arbitrariness of borders and, by extension, of geopolitical allegiances and notions of belonging, of the ways in which identities are forged but also constricted by other powers that be. For Noronha Feio, these ready-made symbols and images upon which cultural identities are constructed and sustained are fodder for an on-going investigation into the fragility and arbitrariness of these geographically, politically and economically bound ecosystems, but also of the strangeness of the power relations at play. At the end of the day, what we take for granted and as a given may not sustain us long-term.

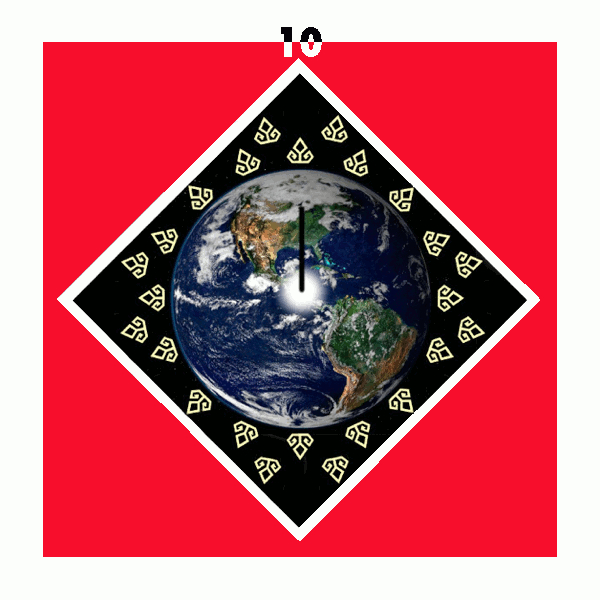

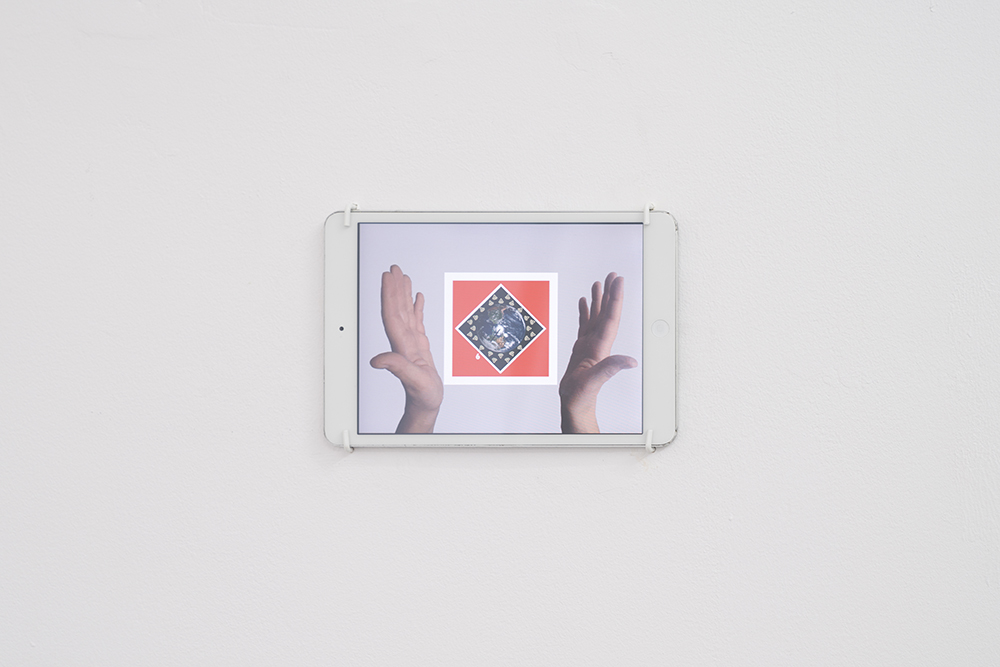

In 1792, the National Convention of the French Revolution, not content with overthrowing the reigning monarchy, set their sights on the measure by which we count out our seconds, minutes, hours and days. The 12-hour clock, inherited several millennia earlier from the Babylonians, was replaced by a decimal system, which included a ten-day week and a ten-hour day. This type of revolution, though, proved too extreme even for those who achieved the downfall of the political status quo, and the system ultimately lasted only for 17 months before the state reverted to age-old, universally ingrained habits. The implication being that difference is all well and good, except when it comes to the old adage that time is money, and in matters of economic growth, production, prosperity and work-discipline, standardisation is the beat which keeps the world ticking in materialist realities. Yet the GIF which reinserts a different conception and framing of time, using a sped-up image of the Earth’s rotations taken from space as its tangential clock-face, tacitly expunges a geocentric worldview.

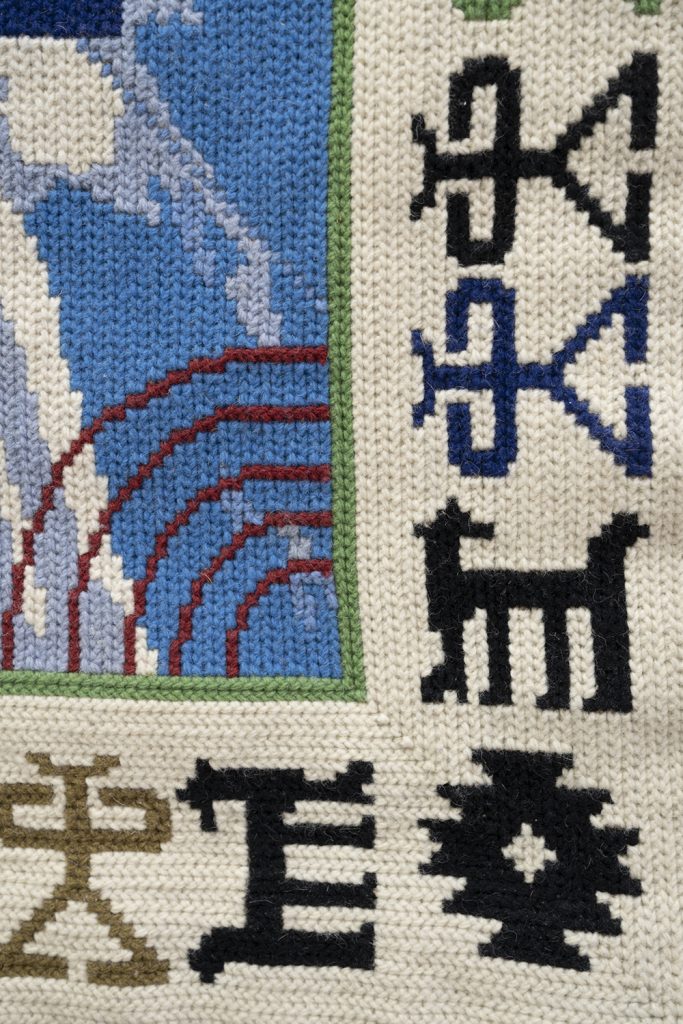

Set against a vividly coloured background of semi-abstract patterns, it mimics the more positively inclined another world is possible (spirituality; good luck; protection; trust; defence; serenity; rebirth; Man) (2017), a rug digitally designed by the artist and produced by Portuguese weavers using a distinct and traditional tapestry technique – Arraiolos – that has been passed on and inherited across generations since the Middle Ages. At the same, their imagery bears a heavy indebtedness to Persian carpets as well as, in more contemporary terms, to Afghan war rugs that have their origins in the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan from 1979 and have continued through subsequent periods of military, political and social conflicts that have persisted. Part of an ongoing body of work, which began in 2008-9, this carpet – alongside its siblings – states itself unconvinced as to the objective truth of any cultural or national mythmaking. Instead, it is a confluence of two civilizations now, as before, seemingly at odds with one another, despite the shared threads that go some way to neutralising their perceived polarisation. Pared down, geometric images of war planes sit against more esoteric signs, the former nosing their way to mirror images of Earth and – what look to be – space shuttles (or, more precisely, Sputnik): microcosms adrift in a cosmic soup. And so we’re back to the universe, an open window to a new world, but one where artificially constructed differences are refashioned as multiplicity through shared commonalities.

– Anya Harrison

Carlos Noronha Feio (Lisbon 1981) consumes, juxtaposes and performs media as research into cultural, local and global identity, adopting culturally significant images, locations and symbols as a form of creative interference with meaning, demonstrating the almost arbitrary nature in which cultural significance is interpreted.

Noronha Feio holds a PhD from the Royal College of Art London and he lives and works in Lisbon, London and Moscow. Noronha Feio’s recent projects include “The Fabric of Felicity” at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, “Futures” at CAC-Contemporary Art Centre Vilnius, “even if at heart we are uncertain of the will to connect, there is a common future ahead” at narrative projects in London, “bathed by the bright light of the sunset” at 3+1 Arte Contemporânea in Lisbon, “Oikonomia: a Matter of Trust” at Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea – Museu do Chiado in Lisbon, “You Are Now Entering_________” at CCA Londonderry/Derry in Northern Ireland, “Image Wars” at Abrons Art Center in New York, and “Da outra margem do Atlântico: alguns exemplos da fotografia e do video português” at Centro Cultural Helio Oiticica in Rio de Janeiro. Noronha Feio’s work is included in the publications “The Art of Not Making: The New Artist/Artisan Relationship” as well as in “Nature Morte: Contemporary Artists Reinvigorate the Still Life Tradition”, published by Thames & Hudson. He is present in several private and public collections including MAAT—Fundação EDP in Lisbon, Saatchi Collection in London, and MAR—Museu de Arte do Rio in Rio de Janeiro.

From 2009 up to 2014 he was a director of The Mews Project Space in London’s east end.

Support: VKKF, VKN

Photos: Līga Spunde